Tribute to Jerry Garcia Intro to Blue Sky

|

| An ad from the December 28, 1973 Hayward Daily Review for the New Year's Eve Allman Brothers concert |

By the end of 1973, the Allman Brothers Band were the most popular touring band in America. Now, it's true that during that year neither The Rolling Stones, nor Bob Dylan nor any member of The Beatles mounted any American tours, but with that caveat aside, the Allmans drew huge crowds like no one else. In particular, when the Allmans were paired with the Grateful Dead, they drew some large crowds indeed. The most legendary of those crowds was the event at the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Racecourse on July 28, 1973, when the Allmans, the Dead and The Band drew an estimated 600,000 people, at the time the largest outdoor rock concert ever. However, earlier in the summer, the Dead and the Allmans had packed RFK stadium in Washington, DC, so it was no fluke.

Given their status, when the Allman Brothers chose to play New Year's Eve in the San Francisco Bay Area at the Cow Palace, it was a benediction indeed, since they could have played anywhere. Yet there was a paradox--wasn't San Francisco's New Year's Eve now the exclusive property of the Grateful Dead? Whether or not New Year's Eve in San Francisco required the Grateful Dead, the paradox was resolved to a national FM radio audience some time after midnight when Jerry Garcia and Bill Kreutzmann joined the Allman Brothers Band onstage. At the time, Garcia's appearance seemed to cement a synergistic relationship between the two bands that became enshrined in rock history. At the same time, it turned out to be the end of an era not just for the two bands, but for a certain aura in post-60s rock, none of which seemed obvious at the time. This post will examine the events leading up to Garcia's appearance with the Allman Brothers on New Year's Eve 1973, and put them into an historical context.

The Grateful Dead: 1973

At the end of 1972, with their Warner Brothers contract expiring, the Grateful Dead had surprised the record industry by refusing to either re-sign with Warners or sign a new contract with another label, choosing instead to go it alone and start their own independent record company. Initially, things had gone pretty well, financially speaking. The Dead had released their new album Wake Of The Flood on their own label in October of 1973. It wasn't a giant hit, officially selling about 400,000 copies, but the band was receiving four times as much money (supposedly $1.22 vs 31 cents for each album sold, per McNally), so they were doing well. Also, the band was a more popular concert attraction than ever, so concert receipts were improving at the same time. In general, the Grateful Dead were in the best financial condition they had ever been up until that time.

Bill Graham had often retailed the story that in 1973 he called the Grateful Dead in the recording studio, asked for Jerry Garcia, and offered the band a New Year's Eve show at the Cow Palace. I first heard Graham tell this story at a free lecture in Berkeley in 1976. If Graham's timeline was remembered correctly, it would have had to have been in August of 1973, when the Dead were recording Wake Of The Flood at the Record Plant. According to Graham, Jerry refused the offer. A shocked Graham said "but Jerry, I'm offering you $75,000 to play the Cow Palace on New Year's Eve!" Garcia reputedly said, "no, Bill, we want to play a private party at your house." According to Graham, when I heard him tell the story, the party was attempted, but it fell through for unexplained reasons. Yet it remains that 1973 was the only year other than 1967 when the Grateful Dead were actively touring, while Bill Graham was alive, when the Dead did not play somewhere.

The party-at-Bill's story has been repeated so many times that everyone takes it for granted. I myself think that Graham was truncating a complex series of negotiations into a single vignette, in order to improve the story. Put another way, the basic arc of the anecdote seems to contain some kernels of truth, but I highly doubt the conversation between Graham and Garcia actually took place in the form he described. To name just a few things, why would Graham call Garcia at the studio? The Dead had a booking agent--Sam Cutler--and while Graham didn't like him, it's unlikely that Garcia would have wanted to discuss business with Bill and thus bypass his own agent. For another thing, would the notoriously disputatious Grateful Dead have had an answer so readily prepared? Finally, in August 1973, Wake had not yet come out, and the Dead's finances would not have been settled yet, and I doubt that they would have been so quick to turn down a big offer without thinking about it.

With all those caveats listed, however, I think the basic dynamic of the story was probably correct. The Grateful Dead were independent, and did not have to explain to a Los Angeles record company why they would or would not play New Year's Eve. Garcia, among others, never spoke fondly of playing New Year's. Finally, by November, when it would have been fish-or-cut-bait time, the Dead would have felt comfortable financially, and willing to tell Graham "no." The business about playing a party at Graham's house sounds like a typical bit of GD snarkiness, suggesting something difficult or ill-advised, just to see if it could happen.

It didn't happen. The Allman Brothers Band, the most popular band in the land, ended up headlining two nights at the Cow Palace on December 31, 1973 and January 1, 1974. It was a tribute to the Allmans drawing power that they could not only sell out New Year's Eve, but sell out the next night also, even though New Years was a Tuesday. Support acts were the Marshall Tucker Band and the Charlie Daniels Band, then both up-and-coming, although hardly unknown. I suspect that the hidden part of the narrative was that at some point Graham must have pitched a joint Dead/Allmans New Year's, but the Dead must have passed. It's also possible that the amount of money required to both book the Allmans and tempt the Dead was too large for an indoor venue. In any case, the Allman Brothers at the Cow Palace were the feature attraction for New Year's Eve in the Bay Area--although the Santana/Herbie Hancock/Malo/Journey show over at Winterland was probably pretty cool--and the Grateful Dead were not working.

|

| The cover to the Allman Brothers hit 1973 album Brothers And Sisters, on Capricorn Records |

The Allman Brothers Band: 1973

Duane and Gregg Allman had first been professional musicians in Florida in 1966, playing as the Allman Joys. They were 'discovered' and moved to Los Angeles, where they led a group called The Hour Glass in 1967-68, and they mostly played around California. They had played the Fillmore and the Avalon a few times (the SF group called All Man Joy had no connection to them), but they never broke out of the 'almost' mode. While in Los Angeles, however, Duane learned to play slide guitar from Ry Cooder and Jesse Ed Davis, and that set his guitar playing apart from almost everyone else at the time. With the demise of The Hour Glass, Duane returned to the Southeast, playing sessions in Muscle Shoals, AL while trying to put a band together.

By 1969, Duane had indeed put a band together, with two drummers and two members of a group called The Second Coming, bassist Berry Oakley and guitarist Dickey Betts. All that was missing was a lead singer, so Gregg was called back from LA (did you know that Gregg had flunked an audition as bassist for Poco?). With Gregg playing organ, writing songs and singing lead, and with the backing of Phil Walden, manager of the late Otis Redding, the Allman Brothers Band was ready to conquer America. With twin lead guitars and two drummers, the Allmans had a unique sound that merged Miles Davis with soul and the blues, and all of the players had been around and were equipped for battle.

I don't think the Allman Brothers owed anything to the Grateful Dead musically, even if Berry Oakley was reputedly a big Deadhead. However, they were based in Macon, GA, and the sixties had come somewhat later to the South. Thus the Allmans adopted the strategy of bands like the Dead, regularly playing for free in places like Piedmont Park in Atlanta, building a loyal audience where they would otherwise have been unknown. Playing for free in the park was old hat in California, but it was a new thing in Georgia. Seeing the natal Allman Brothers Band in mid-'69 for free must have spun around a lot of heads. The Allman Brothers started to tour around, and crowds were knocked out everywhere they went, so every time they came back to a city they had a bigger crowd.

By November 1971, just as the Allman Brothers were breaking out to a huge national audience with their third album, the unforgettable Live At Fillmore East double-lp, leader Duane Allman died in a motorcycle crash. Yet the Allman Brothers Band soldiered on, with Berry Oakley as their de facto leader, and their next album, Eat A Peach, broke them out to a huge national FM audience. Unbelievably, almost a year to the day later, Oakley died in a motorcycle crash himself, not far from the site of Duane's death. Astonishingly, the next Allman Brothers album, Brothers And Sisters, was the band's biggest album ever, behind classic hits like "Rambling Man" and "Jessica."

The Grateful Dead and The Allman Brothers Band, 1969-1973

The Grateful Dead and The Allman Brothers Band crossed paths many times. I do not necessarily think that the individual band members were that close personally. Nonetheless, the bands were kindred spirits in many ways, and great musicians, and seemed to have enjoyed playing together.

July 7, 1969, Piedmont Park, Atlanta, GA

After the triumph of the Atlanta Pop Festival in 1969, which was actually held out in the suburbs, promoter Alex Cooley held a free "thank you" concert in Piedmont Park in Atlanta on the Monday afternoon following the festival. The Grateful Dead were flown in from Chicago. Although the Allmans had played earlier in the day, the Dead would not have seen them play. The Dead closed the show. After the Dead set, there was some jamming, and it appears that Duane and Jerry were both on stage, although no one can confirm if it was at the same time.

|

| The cover for the archival cd Fillmore East, February 1970 by The Allman Brothers Band, produced and recorded by Owsley Stanley and released on Grateful Dead Records in 1996 |

February 11, 1970 Fillmore East

The most famous Dead/Allmans jam, and one of the legendary rock jams of all time, was on Wednesday, February 11 at Fillmore East. The day after was the Lincoln's Birthday holiday. The Grateful Dead headlined over Love and the Allman Brothers. For the late show, the Dead were joined by Arthur Lee (of Love), Duane and Gregg Allman, Butch Trucks and Berry Oakley from the Allmans, and Mick Fleetwood, Peter Green and Danny Kirwan of Fleetwood Mac (in town and hanging out). They played an unforgettable hour long "Dark Star">"Spanish Jam">"Turn On Your Lovelight."

The Allman Brothers Band (and Love) opened for the Grateful Dead on Friday and Saturday, February 13 and 14, but they did not jam. At least one night, members of the Allman Brothers, including Duane, and Love drummer George Suranovich went over to an infamous joint called Slug's to see Pharaoh Sanders. This piece of evidence is one of the clues to me that shows that while Duane enjoyed jamming with the Dead, it wasn't more important than other musical explorations.

November 21, 1970 WBCN Studios, Boston, MA

Boston, packed with college students, was always a hot stop on the circuit for rising bands. It was one of the first Northern cities where the Allman Brothers had a staunch following. On the weekend of November 19-21, the Allmans headlined at the Boston Tea Party. The Grateful Dead, meanwhile, were headlining that Saturday night in the gym at Boston University. Late that night at radio station WBCN, Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Pigpen, Duane and Gregg Allman all stopped by the studio. Ironically enough, there were only two acoustic guitars, so Weir and Duane and then Garcia and Weir played a few numbers, but the tape is more of a curio than anything else.

April 26, 1971 Fillmore East

For the Grateful Dead's final run at Fillmore East, various friends dropped in, one of whom was Duane, who played on three numbers on April 26: "Sugar Magnolia," "It Hurst Me Too" and "Beat It On Down The Line."

July 16, 1972 Dillon Stadium, Hartford, CT

The Grateful Dead headlined a small football stadium in Connecticutt, and Dickey Betts, Berry Oakley and Jaimoe joined the Dead for "Not Fade Away">"Going Down The Road Feeling Bad">"Hey Bo Diddley."

July 17, 1972 Gaelic Park, The Bronx, New York, NY

The day after the Hartford show, Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir joined the Allman Brothers in the Bronx for an extended version of "Mountain Jam." It was around this time that serious discussion began about a combined Dead/Allmans tour. At this time, both groups were popular but not huge live attractions, and both camps seemed to have recognized that sharing a bill would allow them to play much larger places. My own inference is that Berry Oakley, the effective leader of the Allmans at this time, would have been the one most in favor of the Dead and the Allmans working together on an extended basis. An entire tour was actually booked for Fall '72, sadly trumped by Oakley's death. For the scheduled San Francisco dates, on December 10-12, 1972, different acts opened for the Dead, the last time the Grateful Dead had openers at a non-New Years Winterland show.

I am aware that there is some dispute about the date of this show--it was originally scheduled for Thursday July 13--but the entire weekend will be the subject of a future post.

|

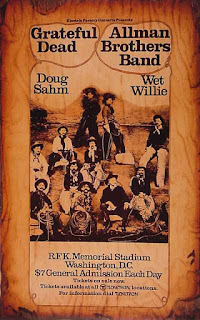

| The poster for the June 9-10, 1973 concert at RFK Stadium in Washington, DC: Grateful Dead/Allman Brothers Band/Doug Sahm/Wet Willie |

June 9-10, 1973 RFK Stadium, Washington, DC

The Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers Band and Doug Sahm played not one but two shows at RFK stadium in Washington, DC, packing both of them as far as I know. These were really huge shows for the era, as full-sized stadium concerts were still quite rare. The fact that the Dead and the Allmans together were more than twice as attractive a bill than either band as headliner was a significant flag to promoters like Bill Graham, who would make multi-act stadium acts a staple of the rock world in the next few years.

On Saturday, June 9, with the Allman Brothers closing the show, Bob Weir and Ronnie Montrose joined the Allmans for "Mountain Jam." For the final set on Sunday, June 10, when the Dead closed the show, Dickey Betts and Butch Trucks joined the Dead and Merl Saunders for an additional set of loosely jammed out songs (as a side note, what was Merl Saunders doing in Washington, DC?).

July 28, 1973 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Racecourse, Watkins Glen, NY

The high water mark for the Allmans was their prominence at the 'one-day' event at the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Racecourse in upstate New York. The auto racing track was the site of the annual United States (Formula 1) Grand Prix (which would be won in 1973 by the great Ronnie Peterson in a Lotus 72 Cosworth), and it could absorb a huge crowd. In response to Woodstock, the state of New York had passed a law banning concerts that lasted more than one day. Thus the "Summer Jam" on July 28 was officially a one-day event, with the Allman Brothers, The Band and The Grateful Dead. The Dead supplied the 60s vibe, and The Band were paragons of credibility back in the day, but the Allman Brothers were unquestionably the big-money headliners, the straw stirring the drink.

All three bands played extended "soundchecks" the day before the official concert, as the crowd was already huge. By the day of the show, the crowd was estimated at an incredible 600,000. Members of all three bands had a loose jam to close the show, playing "Not Fade Away," "Mountain Jam" and "Johnny B. Goode," but it doesn't seem to have been musically memorable.

The Cow Palace, Daly City, CA, New Year's Eve 1973/74

The Allman Brothers Band ended up headlining New Year's Eve at the Cow Palace, with a nationwide radio broadcast. San Francisco's KSAN was the host station, and I think that its Metromedia sister stations, WNEW-fm in New York and KMET-fm in Los Angeles, also ran the broadcast. I gather there were other stations, but I don't know which ones or how many. The broadcast functioned like a nationwide Watkins Glen. San Francisco was still the official capital of "free concerts," even if none had been held in the city for quite some time.

The Watkins Glen concert had in many ways been a last hurrah of the 60s. There was a huge, friendly crowd, bands and promoters made some money, but most people got in for free, the mood was relaxed and a good time was largely had by all. The outdoor jam vibe had been established by the Grateful Dead and their friends in Golden Gate Park a mere six years earlier, and now it was almost outdated. In some ways, the Allman Brothers New Year's Eve broadcast from the Cow Palace was the last high water mark for an avowedly San Francisco style of music, jamming the blues for hours on end as if time had no meaning, with everyone listening for free. In that respect, it was appropriate that Jerry Garcia was there to provide both an actual and symbolic link to the Fillmore and Golden Gate Park.

Live music isn't really free, of course. Some entity, almost certainly Capricorn Records (the Allmans' label) had to have paid for the radio time. Since the Allman Brothers played from about 10pm until 4 am, the cost of the radio time was not prohibitive at that hour. On the East Coast, the time would have been 1am until dawn, an even less expensive time slot, so Capricorn would have gotten some bang for their buck. Nonetheless, the record company would have paid the radio stations for the lost ad revenue, and charged it against the Allman Brothers' future royalties. I assume that the great concert that was played encouraged the sales of a lot of Allman Brothers albums, so it probably worked out OK, but its important to remember that radio broadcasts on commercial FM stations were business propositions.

Garcia's actual appearance on stage on New Year's Eve was paradoxical. On one hand, Garcia continually grumbled over the years that New Year's Eve concerts weren't that fun. Nonetheless, having turned down a lucrative concert date at the Cow Palace, Garcia ended up showing up to play anyway. It goes without saying that the Garcia and the Grateful Dead's peculiar choices were only possible because they owed no allegiance to a record company. At the end of 1973, with Wake Of The Flood selling profitably, the Grateful Dead's financial condition was good, and they could afford to turn down high profile shows on a whim. Yet Garcia seems to have been unable to resist the opportunity to play anyway. He was onstage for around two hours with the Allman Brothers, a full night's work by the standards of regular musicians.

The Music

The concert began with sets by The Marshall Tucker Band and The Charlie Daniels Band, although I'm not certain in exactly which order. At the time, both groups were rising bands that were helping to expand the genre of "Southern Rock" that had come to prominence due to the fame of the Allman Brothers. The Marshall Tucker Band was from Spartanburg, SC and had just released their first album on Capricorn. Charlie Daniels, a veteran session musician and producer in Nashville, had gone solo in 1971. His third album, on Kama Sutra Records, Sweet Honey In The Rock, had spawned the unlikely hit "Uneasy Rider." Both the Tucker and Daniels bands featured twin guitars, hard driving rhythms and country-style vocals.

The Allman Brothers came on at about 10:00 or 10:30, as near as I can determine. The Allman Brothers lineup in 1973 was as follows:

Dickey Betts-lead and slide guitar, vocals

Gregg Allman-Hammond organ, rhythm guitar, vocals

Chuck Leavell-grand piano, electric piano, harmony vocals

Lamar Williams-electric bass

Butch Trucks-drums

Jaimoe-drums

The Allmans played a strong but conventional first set, probably about 70 minutes long (the timings are from Wolfgangs Vault. There was a reel flip between "Midnight Rider" and "Blue Sky").

Bill Graham Introduction 0:36

Wasted Words 5:20

Done Somebody Wrong 6:02

One Way Out 9:50

Stormy Monday 10:11

Midnight Rider

Blue Sky

In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed 17:30

The Allman Brothers Band returned a few minutes before midnight. The first part of the second set was still typical of their concerts at the time

Countdown to Midnight 5:58

Statesboro Blues 5:47

Southbound 7:58

Interlude 0:14

Come And Go Blues 5:20

Ramblin Man 8:22

Trouble No More 4:07

Jessica 13:08

Les Brers In A Minor (Pt.1) 6:21

Drum Solo 11:33

Les Brers In A Minor (Pt.2) 10:32

Les Brers In A Minor (Pt.3) / Whipping Post 14:59

During the last section of the rarely performed "Les Brers In A Minor," (listed above as Part 3), at about 1:15am, Jerry Garcia and Bill Kreutzmann came on stage and started to play. I assume Garcia played the Wolf, but I don't know whether Kreutzmann took over for Trucks or Jaimoe, or played percussion or what. Obviously, this was a planned event. Garcia's equipment must have already been set up, and drummers don't bump aside people on stage without fair warning. In any case, it was apparently a fairly electric moment in the hall, but there was no announcement on the radio.

Garcia and Betts led the band into a jazzy version of "Whipping Post." Remarkably, and possibly uniquely, Gregg Allman never actually sang what at the time was the band's most iconic song. Garcia and Betts sounded great together. Much as I like Chuck Leavell's playing, the Allman Brothers sound needs twin guitars. Garcia played in the more straight ahead, major key style of the Allmans, not really venturing "outside" as he might of with the Dead, but on the other hand he played at the much livelier tempos of the Allmans.

After the "Whipping Post" jam, a radio dj announced that Jerry Garcia and Bill Kreutzmann had joined the band on stage. That must have been a pretty surprising announcement, particularly at about 4:30am on the East Coast, in a post-New Year's Eve haze. For the extensive blues jamming that followed, it appears that Gregg Allman had left the stage, and vocals were handled by Boz Scaggs. Scaggs' connection to the Allman Brothers was probably through his lead guitarist, Les Dudek, a fine Florida musician who had played on the Allmans' studio recordings of "Rambling Man" and "Jessica." By the end of the set, Dudek had joined the jamming as well.

Les Brers In A Minor (Pt.3) / Whipping Post 14:59

Whipping Post 11:57

Linda Lou / Mary Lou 9:56

You Upset Me / Hideaway Jam 17:55

Hey Bo Diddley 28:29

Save My Life 8:44

I Don't See Nothing 10:12

Blues Jam / Bill Graham Announcements 11:22

Somewhere in the middle of "Hey Bo Diddley," the national radio network signed off the air. I suspect that Capricorn had purchased radio time on various stations from 10pm-2am Pacific time, which was 1am-5am in the East, and Tuesday drive time ad rates were kicking in. If anyone was awake on the East Coast listening to this, it must have been pretty frustrating to hear Garcia and Betts jamming away and to find out that the broadcast was being turned over to the morning DJ.

Fortunately, however, for San Francisco listeners, the familiar voice of KSAN's Tom Donahue chimed in after the network signoff and said (more or less) "this is KSAN, and we will be keeping it right here as long as the music is playing." It was this sort of ethos that KSAN seem like the coolest station in the world to its listeners (which it was). By the time the extended second set ended with a variety of improvised blues jams, sung by Scaggs, it must have been pushing 3am. Bill Graham came out, thanked and named everybody, announced that a couple backstage had decided to get married onstage, and--incredibly--announced that the Allman Brothers would be coming back.

I don't know how long the wedding took, and I don't think the third set was broadcast on KSAN, although it's possible. Anyway, it's preserved on Wolfgang's Vault. The final configuration was Garcia, Betts, Chuck Leavell, Lamar Williams, Jaimoe and Kreutzmann. They played three extended numbers, with no vocals. After "And We Bid You Goodnight," it seemed like the show was over, but Garcia and Betts took it into a lively "Mountain Jam," which must have been pretty amazing if anyone was still conscious as the time headed towards 4am.

You Don't Love Me 10:01

We Bid You Goodnight 4:37

Mountain Jam / closing announcements 16:23

Aftermath

After New Year's Eve '73, to my knowledge, no member of the Grateful Dead ever played with a member of The Allman Brothers Band until after Garcia's death. The Allmans played the next night at the Cow Palace, and they were joined at the end with some different special guests--John Lee Hooker, Steve Miller, Elvin Bishop, Charlie Daniels and Buddy Miles--but no members of the Dead. Garcia and Kreutzmann had been booked for New Year's Eve, but other players were there for the next night.

It's interesting to compare the Dead's relationship to the Allman Brothers with their connection to the Jefferson Airplane/Starship crowd. Long after the Dead stopped having too many musical interactions with the Starship, they were still good friends with the various band members. The relationship with the Allmans seems to have been more professional, in an early 70s hippie rock musician kind of way. Both bands were on a high level musically, and the various extended families seemed to get along, which made cooperation easier. It was great business and good musical fun to work together, but ultimately both groups were just people who worked together, rather than close friends.

Source: http://lostlivedead.blogspot.com/2012/12/december-31-1973-cow-palace-daly-city.html

0 Response to "Tribute to Jerry Garcia Intro to Blue Sky"

Post a Comment